Reviews by David Starkey

As I have every year since 2014, in 2025 I set aside a couple of months to peruse the year’s books of poetry–at least those books I had on hand. In the past, I’ve entitled my annual round-up–one review for every day of the final month of the year–something like “Outstanding Books of Poetry.” However, this year I decided to go all in and call the feature “The Best Poetry Books of 2025.” I’m certain there are some excellent volumes I’ve missed–there always are–but I can enthusiastically recommend each of these books to anyone with an interest in contemporary poetry.

While there are plenty of volumes here by the major publishers of poetry, I have, as ever, tried to keep an eye out for superb collections by smaller presses. There are so many good poets out there, and only a handful, sometimes for reasons not entirely related to their poetry, find themselves on the lists of the biggest publishers.

As always, my reviews are intentionally short. Ideally, each one contains just enough information–an appreciative observation, say, or a couple of striking quotations–to kickstart readers into searching out the book under discussion. Happy holidays, and happy reading!

All That We Ask of You Is to Always Be Happy by Bridget Bell (Cavankerry)

If there has ever been a book of poetry that addresses postpartum depression as directly as Bridget Bell’s Alll That We Ask of You Is to Always Be Happy, I don’t recall reading it. In her introduction, medical doctor Riah Patterson states, “these poems capture the essence of perinatal mood and anxiety disorders (PMADs) better than the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders ever could.” And how! There is no easing into the topic. The first poem, “Directive for Women Who Are Not Yet Mothers But Will Become Mothers,” begins: “Soon you will be mired in layers / of din, your body’s smallest bones— // malleus, incus, stapes—stirrup-shaped, will shake / to the sound of phantom milk-cries, so stop // now, while there is still this mercy / of no one needing you.” You can hear in those lines not only the poet’s desperate urgency, but also her incredible gift for sound and image, and nearly all of the thirty-three poems that follow display a similar intensity. This is not an easy book to read, but it is most certainly worth one’s time and effort.

The End of the Clockwork Universe by Fleda Brown (Carnegie Mellon)

Fleda Brown is one of those poets well-known to other poets, superb at her craft, but whose work will also be enjoyed by people don’t who don’t normally read poetry. The End of the Clockwork Universe deals with subjects as serious as the poet’s breast cancer, but even then, she approaches grim topics with an almost amused point of view: “The cancer looked like an unripe blackberry. Or a raspberry. It helps to move from the center of things that way.” In a long poem about Alexander Grothendieck, who, according to Le Monde, was “the greatest mathematician of the century,” she manages to make math interesting for a non-math crowd, and in a series of ten poems called, simply, “Walk,” she brings us into the mind of a walker: “When I’m walking, I am totally inside experience. / It flows by me. I break it into waves.” These poems brilliantly reflect the way a devoted pedestrian will notice something in the landscape that ignites a seemingly unrelated string of thoughts, which ultimately, circle back to the physical act of putting one foot after the other and moving forward on the earth.

Collected Poems by Wendy Cope (Faber)

Wendy Cope is big in Britain, where poetry isn’t quite as sidelined from the literary mainstream as it is here in America. You can see why. Her poetry has a sense of humor, without being merely silly—a rare quality in verse from any era, much less our own. Over nearly five hundred pages, Cope creates a world that is whimsically sad, but not too sad, where the legacy of a deceased relative is “the suit / My teddy bear still wears, / And fifty pairs of woolly socks / In drawers all over England.” Among the book’s treasures is “The River Girl,” a long poem illustrated by Nicholas Garland, which tells the wry, unhappy story of the poet John Didde and Isis, a mermaid from the River Thames. Didde comes out looking like another word that begins with “D,” and there’s a lot of needling of poets in Cope’s Collected Poems, especially men: they are, we learn, a vain species given to self-pity and resentment over the fact that they and their work will inevitably be forgotten. Still, along the way, Cope is bound to have some fun, as she does in “Another Christmas Poem”: “Bloody Christmas, here again. / Let us raise a loving cup: / Peace on earth, goodwill to men, / And make them do the washing-up.”

Heirloom by Catherine-Esther Cowie (Carcanet)

An heirloom is a valuable object passed down through the generations, but the heirloom in Catherine-Esther Cowie’s first book seems more like a human quality: persistence in the face of racism and sexual assault. One of the book’s epigraphs, from René Girard, declares: “All cultures and all individuals without exception participate in violence…violence is what structures our collective sense of belonging and our personal identities.” That’s a pretty sweeping statement, but it’s borne out by the poetry in Heirloom. Time and again, the four generations of Santa Lucian women in the book must face the consequences of brutal non-consensual sex: “Isn’t that how most of us / came to be?” asks the narrator of “Elegy.” “Not out of love / or rightness. // But hips banged open. / Forced.” And yet for all of its grimness, Cowie’s poetry strives not only to make sense of the violence and disappointment, but to overcome it by naming the truth: “the jolt of electricity you feel / when you flick the switch / on and off, on and off, / is real, real, real. / Trust the knowing of your flesh, / a body that refuses to lie.”

Sweet Repetition by Cynthia Cruz (Chicago)

With lines like “The television static has been playing / The same Maria Callas / Song for days, for centuries” and “Death on the line, / Murmuring its obscene / Numbers” and “I had a fellowship but lived poorly / On cheap beer and penny candy” and “Lottery tickers and plastic bags of glass / Bottles, barefoot in a cream-white / Evening gown and silver halo / Of paper cutout stars, I began speaking / In a language I could no longer comprehend,” it’s clear that Cynthia Cruz’s Sweet Repetition is determined to come at the world from a canted angle, a perspective that is by turns surreal, droll and slightly terrifying. The book contains four poems each with the titles “Nachtstilleben” (Night Still Life) and “Charity Balls.” The former evoke a kind of moody nostalgia, while the latter, subtitled “After John Weiners,” the avant-beat poet who died in 2002, have an edgy whimsicality. The “Charity Balls are an especially rich source of memorable lines: “I had an accident but lived in elegance / On methamphetamines, and small stacks / Of Black Beauty paperbacks, / Plastic plates of bread, / And black cherry marmalade.” As Sweet Repetition suggests, it’s not just poem titles that repeat throughout the book, but also images, ideas and emotional states, all of which grow richer upon rereading.

Stock by Jennifer Bowering Delisle (Coach House)

The Stock of Jennifer Bowering Delisle’s new book is stock photography. In an afterword, she writes that “Stock’s low-cost model means that stock imagery is ubiquitous in our lives. It is a reflection of what (or who) is valued, of biases and privileges. In turn, stock imagery shapes, if only subconsciously, how we as a society interact and even define ourselves and each other.” Bowering Delisle’s response to the power of stock is to do everything she can in her poetry to undermine it. Frequently the poems begin with the bracketed word “Search,” but what the poet reports about the images returned in any individual search is miles away from the visual clichés one might expect. Just one example, from “[Search]: Spring,” which nods, in part, on Shakespeare’s Sonnet 18: “Bouquets on barnwood and bokeh on buds. / Cherry blossom toothache. / Where is the brown grass matted with mould / and sand of winter’s traction / the mophead shrubs, runoff lit / by littered foil, not the yellow of little boots?” The repetition of this trick might have grown old, but Bowering Delisle has a knack for innovation and comedy, so it never feels as though she is belaboring her central metaphor.

The Furies by Moira Egan (LSU)

One of the best living formalist poets writing in English, Moira Egan composes poems that are elegant, intelligent, pitch-perfect and not infrequently more than a little angry. “Of course you’ve heard the joke,” she writes in the title poem, “Anonymous / was woman, woman-born, to take the piss; / her silly work: the critic’s piss upon it.” And in “Velar,” which plays on the consonant sounds made when the tongue touches the soft palate: “She said that faith is her anchor / but I heard anger.” And later in the poem: “Disruptive to systems, anger / or anchor. // Both velar. One voiced, / one voiceless.” Egan’s subjects are often familiar stories about women, largely from Greek mythology, but with allusions to everyone from Karen Blixen, author of Out of Africa, to Rapunzel and Artemisia Gentileschi and Mary Magdalene. Her “plague poems” are especially poignant and well-crafted. “Lemons” reads in its entirety: “Citrine rings of sun / steep in hot water, / the blue-and-white china cup / a gift from a friend. Distant. / We are all distanced. / No one is immune.”

Ungrafted: New and Selected Poems by Claudia Emerson (LSU)

Claudia Emerson died of cancer eleven years ago, at the age of fifty-seven, so one might have thought we would see no more “new” work from her. However, editor Dave Smith presents us with “twenty-six of her forty known previously uncollected poems.” I’m not sure what the issue was with the other fourteen, but if they are anything like the uncollected poems presented in Ungrafted, I would love to read them. Emerson was particularly gifted in presenting a complex analogy in precise terms. In “Learning How to Dive,” the narrator “imagined / Myself a bow, a blade // Of flexed tempered steel—or water pouring / From an invisible pitcher, returning // To itself.” As for the previously published poems, they continue to read as the work of a master of sound, imagery, metaphor and, that essential Southern quality, tact. “The Cough,” about the death of her husband’s late wife, concludes: “[The cough] would outlive the locusts, but by days few / enough to count—the translucent forms still left / clinging to the world they had overset, / each one a perfect mold of the body that refused it.”

Six White Horses by Sarah Gordon (Mercer)

“Ambiguous Loss” is a not atypical poem in Sarah Gordon’s Six White Horses. The title, the epigraph tells us, refers to a “term given by psychiatrists to describe the emotional state of those who do not know whether their lost loved ones are dead or alive.” “For starters,” the poem begins, “the missing cat. / Soon enough, high school pals, / college boyfriends, harmless / rivals, that beloved professor / you thought you’d never forget, / glasses strung on a cord around / her neck, that imposing gaze.” But Gordon’s poems, even if when they begin in the domestic and daily, are always looking to transcend the ordinary. And so in “Ambiguous Loss,” she soon turns her attention to the “hordes foraging / for food in the desert, bending / over the burning earth in desperate / prayerful attendance.” It’s a strategy she uses to great effect as she writes about war, friends who have died, eccentric relatives, The Book of Kells, “Memory, that Bitch,”and the “many breathing sneezing / bodies in the metro // trying to stand without / expression or touch.” Gordon gladly admits she doesn’t know all the answers, but that doesn’t prevent her from trying to “see more / clearly who the hell we are.”

What God in the Kingdom of Bastards by Brian Gyamfi (Pittsburgh)

Brian Gyamfi has a real gift for description. Take, for instance, the opening lines of “Horseradish”: “Midnight in Accra and the crepuscular chills / seem sweeter than we believe a breeze should be, / like the moment horseradish ferments into honey. / In the afternoon, I saw Ama again by a crate of drinks / and her collarbone spread like jam on bread.” However, his real gift in What God in the Kingdom of Bastards is a kind of playful semi-surrealism. In a “Poet Travels to the South,” he riffs on the sort of experiences a first-generation Ghanaian man might have in the region: “In one restaurant I found Jesus. In another, / a mobile phone. Hello, / my visa is on fire. My English is limited, / but my friend speaks it beautifully. / Let me give him the phone.” The book’s subject matter is often serious, but Gyamfi’s secret weapon is his brashness and sense of the absurd, which he brandishes with deadly effect throughout: “In my stomach the ancestors carry water to stones. / And I swear I’ve watched an eagle walk in its morning shit.”

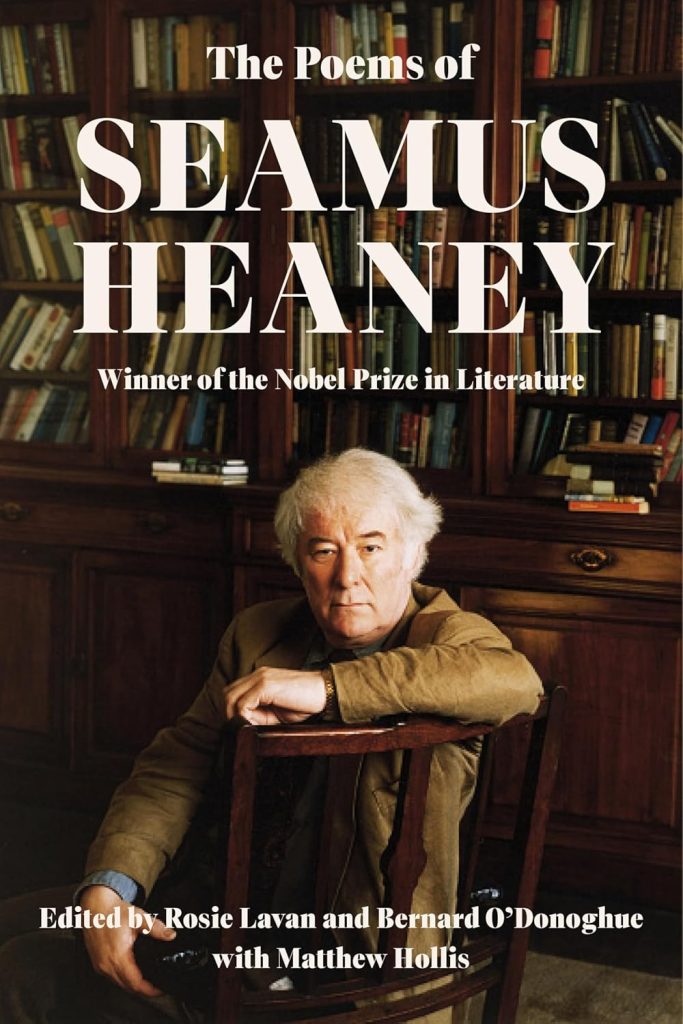

The Poems of Seamus Heaney (Farrar, Straus and Giroux)

On my desk, just to the left of my computer, sits a boxed set of all Seamus Heaney’s books, which I purchased at the Seamus Heaney HomePlace in Bellaghy, Northern Ireland. The spines are faded from the sun, and my favorites—Wintering Out, Field Work, District and Circle—are starting to fall apart from having been read so often. Over the years several Selected Poems have appeared, but I’ve been waiting a good long while for the full Collected Poems, and here it is. I won’t say, “Be careful what you wish for,” as this is a magnificent book, one I would recommend without hesitation to anyone looking to own some of the world’s best poetry. And yet what makes The Poems of Seamus Heaney so magisterial is the very thing that ensures I’ll keep my Faber & Faber boxed set where it is, as the new volume feels as though it’s meant more for scholars than general readers. Most noticeably, the line numbers of the poems are given in the margins, and whereas, in the original volumes, each poem, even the very short ones, had their own page, here one poem follows hard upon another. There are eight published but previously uncollected poems, and twenty-five unpublished poems, chosen by the Heaney family–a treat, to be sure–but what’s most noticeable about the book’s second half is the massive commentary section, well over 500 pages, if you count all three appendices. That said, there is nothing on earth quite like these poems, however they are packaged.

Naked Ladies: New and Selected Poems by Julie Kane (LSU)

A former Louisiana poet laureate, Julie Kane offers more than a little spice in this collection of well-crafted and radiant poems. The selections from her previous books tend to have a thematic focus, which means they sometimes read almost like short stories. Rhythm and Booze, for instance, contains some excellent poems about bartenders and drinking in general, while Mothers of Ireland offers a veritable family history of strong women emigrating to America from the old country. Kane is drawn to forms, so there are pantoums, sestinas and plenty of sonnets and villanelles; not infrequently, she uses rhyme to wry effect. In fact, repetition with a difference nearly always works in her favor, whether she is laughing or deadly serious, as in the final stanza of a villanelle entitled “The Scream”: “The monster was still there when I awoke; / No earthly weaponry could bring it down, / Those years I had a scream stuck in my throat / Until I spoke my truth and did not choke.”

Parallax by Julia Kolchinsky (Arkansas)

“It’s easy to look away from war,” Ukrainian-American poet Julia Kolchinsky writes in the villanelle “One Year Later,” “when your wallet’s empty and sink is full / when the land and people aren’t yours, // when your children scream for more / of you, when your body’s pulled / it’s easy to look away from war.” That poem, which focuses on both child-rearing in America, and the distant war in Ukraine touches on two of the most important themes in Parallax. The title alludes to the way the position of an object differs depending on where we view it from, and Kolchinsky examines her life, and those of family members left behind, from multiple angles. It’s a painful experience, without consolation: “Even now, writing it / feels like the opposite. I guess I’m referring / to distance.” She tells us in “Two Years Later, “The last thing I want is another poem / about war and dead children and how / we’ve forgotten their names.” But that is the poem she must write, again and again, in this difficult but worthwhile collection.

The Old Current by Brad Leithauser (Knopf)

There’s something irresistible about light verse in the hands of a master like Brad Leithauser. Take, for instance, “What to Believe: A Biblical Exegisis”: “The garden of Eden? / Maybe a fable. / Yet you can be certain / Cain slew Abel.” Or “Anonymous’s Lament”: “Though love (it’s been said) is a perilous game, / At times I might wish to be bolder— / Just once to be either the moth or the flame / And not the candle holder.” Not all the poems in The Old Current are quite so funny and epigrammatic. There are a several longer autobiographical reminiscences, in rhyme, naturally, and often poems that begin in fun end on a more somber note, such as “End of an Adventurer”: “He’s ridden on a camel’s back, / In a bathysphere, a glider, a sealskin kayak, / A dhow, a dogsled, and now a gurney, / Silent and smooth, for the final journey.” The best rhymed verse improves upon acquaintance, and I enjoyed The Old Current a little more each time I read it through.

Archive of Desire by Robin Coste Lewis (Knopf)

Regular readers of these annual round-ups know that I am not a big fan of the long poem, but Robin Coste Lewis’s Archive of Desire manages to sidestep most of the drawbacks of the genre: grandiosity and pomposity; awkward gaps in time, space and place; and book-length metaphors stretched so thin that they can’t help but snap. Subtitled A Poem in Four Parts for C. P. Cavafy, the book began as a collaboration with the great jazz pianist and composer Vijay Iyer, cellist Jeffrey Zeigler, and visual artist Julie Mehretu. That would certainly have been quite a performance to attend, but what we do have is an opening longish poem that combines autobiography with subtle allusions to the Greek-Egyptian poet Cavafy; a section of “Cavafy in Fragments/An Erasure”; a short poem entitled “Cavafy in Compton/Closet Anthem: Self-Portrait at Sixteen, 1979,” which begins, “I came out / of the office // where I had been / hired in another shitty, low-paying job”; a prose poem subtitled “Self-Portrait as the Acropolis”; and a prose epilogue reflecting on the poet’s childhood and the constraints of traditional gender roles: “I think it was Whoopi Goldberg who once said homosexuality is as old as air. And I think it was Freud who said that heterosexuality is the actual anomaly.” Somehow, it all ties together in a work that truly lives up to its title.

Startlement: New and Selected Poems by Ada Limón (Milkweed)

A United States Poet Laureate inevitably takes on a certain mantle of seriousness, so it’s refreshing to revisit Ada Limón’s body of work and be reminded of how high-spirited so much of her work has always been. Startling, too—as the book’s title suggests. I kept underlining passages that leapt off the page. From “First Lunch with Relative Stranger Mister You”: “My fist is like a kiss.” From “The Vulture & the Body”: “On my way to the fertility clinic / I pass five dead animals.” From “Field”: “To consider him with horses is to consider him / as himself. He doesn’t notice much else.” There are plenty of lines in this outstanding collection that could serve as Limón’s ars poetica, but I like the opening of “The Endlessness”: “At first I was lonely, but then I was / curious.” Throughout Startlement, the sorrows and disappointments of life pale in comparison to Limón’s interest in exploring them in her poetry. One early poem, “Little Day,” here in its entirety, sums it up nicely: “This is what it comes down to: / Me on a park bench, always writing. / This is what it comes down to.”

Cold Thief Place by Esther Lin (Alice James)

Esther Lin is the daughter of a difficult mother. The fact that her mother emigrated from China to Brazil, where Lin was born, and then onto the United States, where her mother, believing the world was going to end, did not apply for citizenship for her children, makes the story all the more complicated. Now that her mother has died of cancer, Lin is able to look back on her life more fully, though not without a great deal of pain. She writes in “Up the Mountains Down the Fields,” a slogan of the Chinese cultural revolution: “I asked / what were / the happiest / of your days / and you didn’t say / us I knew that / already / I didn’t mind / but you said / the revolution / nobody / says that.” Lin’s personal history, like anyone’s, is peculiar to herself, but she writes so well that it soon feels universal. And yet, always lurking in the background, is her uncertain status as an American. “Illegal Immigration,” the poem of that title tells us, “is the absence of a paper / and the presence of a person. // A person with pages and pages / documenting her movements // is a convict. / Or undocumented.”

The End of Childhood by Wayne Miller (Milkweed)

There are three poems in The End of Childhood with that title, and, in fact, the entire book is more or less about coming to grips with loss of innocence. Many of the poems are written in free verse couplets, so that Wayne Miller’s complex ideas and stories can be read quickly. You’re often finished with a poem before you realize its heft and have to go back for a second or third time. In “Camoufleurs,” to take just one example, we learn about André Mare, a minor French painter in the First World War who used “the decorative / application of cubist principles” to obscure “objects on the ground / from the new, godlike planes // that could read the world below them.” The poet recalls being obsessed with camoufleurs as a boy when he and his friends would play war, shooting BB guns at one another in the local woods. The metaphor is then applied to poets who “use their art / to obscure themselves, to disappear // behind the details they’ve gathered / from the world around them.” The various strands are then tied together when we learn the poet’s best friend had been abused as a child in a home that served as “a screen / none of us could see through.” As in his previous books, Miller continues to write with intelligence and devastating clarity.

Regaining Unconsciousness by Harryette Mullen (Graywolf)

Readers averse to slim volumes of verse, where each small poem sits on the page like a cameo brooch, will be heartened by Harryette Mullen’s Regaining Unconsciousness, which contains a hundred and forty pages of rollicking, innovative poems. Mullen, author of the aptly named Sleeping with the Dictionary, embraces language, but she also wrestles with it, mocks it, bamboozles it, and isn’t afraid to give it a good talking to when it’s out of bounds. Among my favorite poems in the book are “Land of the Discount Price, Home of the Brand Name,” which begins: “My large magnetic car flag proudly displays Old Glory / as I drive to Family Dollar for the makings of a Fourth of July picnic. // I pledge allegiance to my Mastercard / that is honored in more stores than American Express.” And then there’s “Sonnets Composed on a Loo Roll,” a prose poem full of sonnets written on an unspooling roll of toilet paper during the pandemic. It’s comic, to be sure, but it also asks hard questions about the service workers forced to “move the food, tote those boxes, stock those shelves.” The poem ends: “Oh yes, we need loo roll, too.”

The Map of the World by Eiléan Ní Chuilleanáin (Wake Forest)

Eiléan Ní Chuilleanáin rarely disappoints. Her work hums with the rhythm and music and wit of the best Irish poetry in English, though there is something a little sharp and bitter that makes Ní Chuilleanáin’s work distinct. The poems’ subjects are diverse. There is Milton hearing Mozart on a mountain in the underworld: he “climbed wearily on the corpse of Cromwell / to emerge in a greying dawn.” Noah builds his ark in the face of impending environmental catastrophe: “staring everywhere at once / like a wild thing cornered, even though for ages / all around him there has been nothing but the flood.” The poet arrives in Italy during the pandemic, where the taxi-driver overcharges her, and the people at the hotel, she tells us, “remember me / but also, as before think I am German—because of my hair?” Three of the poems are in Irish, though I was able to translate them using my phone. Even in the shaky shorthand of Google Translate, the poems were pretty good—perhaps the ultimate accolade for a twenty-first century poet.

Kitchen Hymns by Pádraig Ó Tuama (Copper Canyon)

The Irish poet Pádraig Ó Tuama is perhaps best known as the host of the Poetry Unbound podcast, which takes a deep dive into a single poem in each episode, but he’s also a fine poet himself. His poems can be jokey and colloquial, as in “Jesus and Persephone Meet After Many Years.” They discuss resurrection, naturally, with Persephone asking the Messiah: “Hey, I always meant to ask you—is there more / than just one way?” And then there’s “[untitled/missæ],” the final poem in the book, which praises “the deer and ox, / the heron and the hare,” and a host of other animals, concluding: “I go in the name of all of them, / their chaos and their industry, / their replacements, their population, / their forgettable ways, their untame natures, / their ignorance of why, / or how, or who.” Several times in the second half of the book, a black page appears with white text at the bottom, a kind of reminder that poems can manifest themselves in very different ways. “Why are your mercies new every morning?” one of these poems asks. “Do they leak away at night? To where?”

Towheaded Stone Thrower: The Harriet Poems by Jim Peterson (Press 53)

Harriet, Jim Peterson’s late wife and the subject of Towheaded Stone Thrower, was, the book tells us, an incredibly complex person—fierce and passionate and fun-loving—but above all she was a rider of horses: “You ride deep in the saddle, balanced, / hands on the reins in ready contact / with his sensitive mouth, allowing / his head and neck to reach out, / relaxed, muscles flowing, ears alert / and forward, your legs bowed / to the flanks, eyes focused ahead // on the forest trail or the open field / seeking an obstacle—a wall, a fence, / a gully—to fly across, hooves churning / beneath you like cogs in the wheel of the earth.” You can tell how much Peterson loved his wife by the detail and intensity of this description, and passages of equal beauty occur throughout Towheaded Stone Thrower, surely one of the great paeans to a departed spouse—in this case someone who was only satisfied when “her wildest / dreams of being are wreaking holy havoc in this world.”

Collected Poems by Stanley Plumly (Norton)

In his introduction to the Collected Poems of Stanley Plumly, David Baker (co-editor with Michael Collier), identifies three important traits of Plumly’s poetry: 1) “he invests the lyric poem with narrative ‘values’… From the beginning Plumly is a storyteller”; 2) “the figure, poetry, and example of John Keats…accompanied Plumly through the mature years of his writing”; and 3) “his conversion of poetic form into the unmistakable features of his style, his poetic self.” As I read through the book, I could see those qualities, but what struck me most was the variety of Plumly’s responses to the world. Like Ted Kooser, Plumly appears able to turn just about any memory or experience into a poem, though unlike Kooser’s work, Plumly’s poems rarely feel, at the end, as though all the parts are clicking into place. Instead, the poems open outwards, Whitmanesque, as in the second part of “Two Poems”: “In one dream I see my back-breaking father / at the wheel. He is grinding bone / back into dust. He looks like a miller / covered in flour. He works / his shift only to lie down / among the million / upon million / and rise again, / individual to the wheel.”

Monk Fruit by Edward Salem (Nightboat)

In Monk Fruit, Edward Salem is never short of a clever verbal jab. “Calm emanated from the old swami I met,” he writes in “Final Montage.” “His B.O. did, too.” Not infrequently, he is the target of his own ire and irony. In “Species Dysphoria,” he writes: “I give interviews about my death / on first dates. // I don’t die, / I just eat a lot of salad.” However, as the son of Palestinian parents, he reserves his sharpest barbs for Israelis and their allies. In “The Animal,” “Death is almost as humiliating / as going through Ben Gurion Airport. / The pleasures of return are worth it, though.” A poem about failed attempts to fast for Gaza ends: “Jenny Craig should advertise with Al Jazeera.” There’s a dark humor in many of the poems, but sometimes it vanishes, leaving only pure anger. “Told You Obama Wouldn’t Close Guantanamo” is spoken by an innocent victim of torture: “They cut a Star of David / into my forehead / with a boxcutter. // My blood filled my eyes. / The salt of it stung. / My eyelashes clotted.” Then there’s “Prop Comedian”: “To God, the new Nakba is / a watermelon smashed with a sledgehammer / in Her schlocky comedy act.” If this is the future of political poetry, I welcome it.

We’re Somewhere Else Now by Robyn Sarah (Biblioasis)

The topic of the poems in Robyn Sarah’s We’re Somewhere Else Now vary, though a number of them touch on the pandemic, which, due to the long lag between the time a poet writes a poem and a book appears, is a subject much in evidence in poetry books this year. Sarah gives us “Shadows in Springtime,” dated May 2020, which begins, “Little boy, grandchild I waited / so long for, / play with me. / Play / six feet away, six feet / too far away.” And “In Lockdown,” set in Montreal in 2021: “On a village lamp post at the corner of Parc / and Villeneuve, someone has printed / in permanent black marker / NO HAPPINESS EVER.” Yet one of the book’s projects is to find happiness, especially when it’s not in plain view. And so We’re Somewhere Else Now is full of moments when the poet translates loss into consolation, as in “On Reading Hopkins’ No Worst, There Is None…”: “A single soul’s relief, and not for long. / Is the cry of grief, out of the belly torn. / But solace for generations yet unborn / Is the grief-cry channeled into poem or song.”

I Do Know Some Things by Richard Siken (Copper Canyon)

Louise Glück chose Richard Siken’s first book for the 2004 Yale Series of Younger Poets prize. His second book was published in 2015, and after ten years, we finally have his third collection–it’s no exaggeration to call this book “long awaited.” I Do Know Some Things consists of 77 prose poems, and no matter what story each one tells about the poet’s complex life and ruminations, it nearly always begins with a memorable first sentence. “Real Estate”: “My mother married a man who divorced her for her money.” “Family Therapy”: “The morning after my father killed his first wife, he woke up next to her dead body, rose from their bed, and began his morning routine.” “Heart Failure”: “My grandmother would put on lipstick before playing solitaire.” And those are just the openings of the first three poems. The biggest narrative through-line concerns the misdiagnosis of a stroke Siken suffered as a panic attack, and the inevitable complications that follow. Yet whatever happens, Siken maintains not only an astonishingly clear recall of the details but also a saving sense of irony. In “Heat Map,” “The neurologist takes out a folder, a picture. He points at my brain with a finger, says here. It looks like a map of a city on fire, a snapshot of weather. It creeps me out.”

The Intentions of Thunder: New and Selected Poems by Patricia Smith (Scribner)

In The Intentions of Thunder: New and Selected Poems, winner of this year’s National Book Award for Poetry, Patricia Smith uses irony to devastating effect in poem after poem. “Emmett Till: Choose Your Own Adventure,” begins: “Mamie Till had hoped to take her sone Emmett on a vacation to visit relatives in Nebraska. Instead, he begged her to let him visit his cousins in Mississippi. // Turn to page 194 if Emmett travels to Nebraska instead of Mississippi.” The poem appears on page 194 of The Intentions of Thunder, and the sonnet that follows describes Emmett dozing in his mother’s Plymouth as they traverse the “country’s hellish breadth.” When they have to stop, and he must face down the racism of the small-town hicks running the local stores and gas stations, he maintains the swagger that some say led to his murder in Mississippi, but in this alternative history version, “he’s learned to turn their threats to anecdote / and chuckle at the squeeze that begs for his throat.” In short, he survives, as do so many of the protagonists in The Intentions of Thunder. Despite the heaviness of its subject matter, this big, inventive volume is ultimately a book of triumph and even joy.

Shade is a Place by MaKysha Tolbert (Penguin)

In “Shade is a place: an urgent need,” MaKshya Tolbert writes, “I take up listening. It takes a long time, / the rearranging. You could say this city / is a tree: an open center penetrated by light. // You could say shade is my refuge, this compass of what matters.” These lines might sound rather mysterious, but they are less so when you know that Tolbert’s book is drawn from her experience as both an Arts Fellowship Guest Curator and chair of the Charlottesville Tree Commission. Her project became to lead citizens of that Virginia town, with its unsettled racial history, up and down the Charlottesville Mall, where the urban willow oaks were stressed and dying. The book is a record of those “tree walks” and “shade walks,” an attempt to create a “Black sense of place.” Ultimately, Tolbert’s most successful rendering of the experience is in a series of haibun and haiku toward the end of the book: “Time to organize my trees. A green book for walkers. Each willow oak we visit is as much text as textile, woven through steel and clay. I always kept a diary, now I show up as a haibuneer: / sunny living rooms / fragile songbirds eye sunlight / shade shows just in time.”

The Cave by Ryan Vine (Texas Review)

If you were wondering if the cave of this book’s title was, in fact, Plato’s cave in Book 7 of The Republic, all you’d have to do would be to flip to the end, where there is Afterword from poet Ryan Vine explaining that Plato’s allegory “is a guiding metaphor for the way in which I organized the poems.” Plato’s five-page passage from The Republic, translated by Vine’s colleague, comes next, and, in turn, is followed a full-page note from the translator. It all seems a bit much, so I’m glad I didn’t come across it until after I had finished reading the excellent poetry in The Cave. The majority of the poems are about what it’s like to be a young father, a subject greatly neglected in our literature. Vine doesn’t shy away from the awkward moments of child-rearing, but he clearly loves his son and daughter, and his family life seems mostly to be a happy one. In the final poem, his daughter squeezes his hand, and he thinks: “for most of my life / I’ve wanted language always / to accompany me but for right now I’m good.”

Hindsight by Rosanna Warren (Norton)

I don’t believe Rosanna Warren could write a bad poem if she tried. in Hindsight, her seventh book, she continues to compose verse that is rich in sound and imagery. Just two examples. “For a New Year”: “Off the paved road, down the dirt track / past trunks of felled ash trees, a crazed giant game / of pick-up sticks jumbling the woods, we come // to the reservoir. The path ends / in the lisp and murmur of wavelets tonguing stones.” And “Still Life,” about the poet as a young woman, “eighteen // and virginal”: “Not silk roses, but two mackerel / purchased that morning at the stall in Campo de’ Fiori / silver but tarnishing / fast slumped across a plate // I’d set up for art. Their eyes blurred. / Art filled the apartment / with odors of turpentine / and decomposing flesh. Their gills // sagged.” It’s not just the vivid visual descriptions here, but the sounds (“the lisp and murmur or wavelets tonguing stones”) and smells (“odors of turpentine / and decomposing flesh”) that pull the reader into the poem, whatever its subject matter. As Coleridge said, “the best words in the best order.” Far easier said than done.

Blue Loop by AJ White (Georgia)

The brief author preface to AJ White’s debut collection, Blue Stars, promises a book of extremes and volatility: “A blue loop is the life of a star when the star evolves from cool to hot before cooling again. Stars executing blue loops cross a graphical region called the instability strip because the outer layers of stars in the category are unstable & pulsate. Blue stars are the hottest stars of all.” This metaphor haunts the book, though its most striking poems aren’t about stars at all, but about White’s battle against alcoholism, which, come to think of it, is something of a “blue star” in itself: “we were at a party in Nashville I had been trying to drink less so of course I drank more ruined everyone’s night then I stayed up for hours whispering in your ear I hate you I hate you until you turned to me crying you had been awake the whole time you asked why I hated you & I did not yet know it was because I hated myself.” If there’s a quiet triumph in ultimately sobering up, there’s also a loneliness pulsating through many of these poems—before and after sobriety. Just look at the conclusion of “End of February, Helen Street”: “Nightfall, & the moths draw down / their inheritance of moonlight. // You are right not to want to be, / not to want to be alone.”