Penguin

Review by Walter Cummins

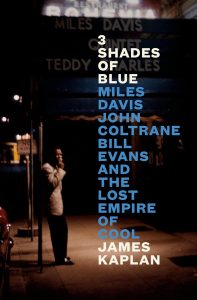

Despite the depiction of the many triumphs of three of the greatest jazz musicians—many might argue of musicians in any genre—3 Shades of Blue is a painful book to read as it integrates the tormented lives of the men with their musical mastery. Was there a unity of man and music? Were their sufferings essentially bound to their creations—the price of the fulfillment of genius?

I hope not. To believe so would be to romanticize addiction, an assumption made by the many jazz musicians who attributed the wonder of Charlie Parker’s playing to the highs of his habit and chose heroin in an attempt to emulate him. That includes almost every major jazz musician of the mid twentieth century.

Some went to jail. Many more died young. Kaplan inserts lists of the short life spans of the those whose living and playing was limited to just a few decades. Bill Evans’ reaching fifty-0ne was an extended longevity when compared to the number of others who didn’t make it out of their twenties and thirties.

It would be preferable to conclude that drugs were nothing but a negative, that Charlie Parker, Miles Davis, John Coltrane, Bill Evans, and all the others could have matched drug-free Dizzy Gillespie’s seventy-five, playing brilliantly and even evolving for many more decades.

I hadn’t realized how much Miles Davis, addicted to heroin, struggled in the early 1950s, with few recording dates or bookings for live performances. My faulty assumption was that he hit New York as a teenager, dropped out of Julliard, joined Charlie Parker’s group at nineteen, and just went on to greater and greater innovative fame. It wasn’t like that. Kaplan depicts him strung out in shabby clothes, desperate for work, all he earned going for drugs. For example, he was lucky to get a gig with Howard Rumsey’s Lighthouse All-Stars in Hermosa Beach, California. He even recorded an album with that group that I found on Apple Music. The trumpet sounds nothing like the controlled, masterful Miles Davis I expected. It was tentative and sloppy, with just a few strong riffs. Unlike Charlie Parker, who could solo brilliantly minutes after a needle in his arm, heroin undermined Miles’ genius.

Yet, as Kaplan explains, the musicians were aware of the choice they had made. According the trumpeter Red Rodney, “Heroin was our badge. It was the thing that gave us membership in a unique club, and for this membership we gave up everything else in the world. Every ambition. Every desire. Everything. It ruined most people.” Sonny Rollins, who defeated the habit, saw a special rebellion in heroin for Black musicians: “So it was our fight against discrimination, our way of fighting against American culture.” Yet Kaplan finds a very heavy price paid: ‘John Coltrane, with his persistent quiet sadness, the haunted air that’s so striking in photographs, seemed to be in the grips of physical and emotional forces he was nearly powerless to resist.—”

Kaplan’s book made me wonder how much insecurities about their fulfilling their talents resulted in an escape to the crutch of drugs for Davis, Coltrane, and Evans. Even though millions have acknowledged that they were special, as young men in their twenties they were overwhelmed with doubts.

After his time with Charlie Parker, Davis struggled to maintain his musical voice. In his words, “I had a heroin habit that took me four years to kick and I found myself for the first time out of control and sinking faster than a motherfucker toward death.” According to Kaplan, in 1955 Coltrane was “an awkward outsider, as far as possible from any kind of distinction in his field.” Saxophonist Benny Golson says of the young Bill Evans, “I truly cannot fathom how the great musician he became could have originated from that.”

Yet their talents soared in just a few years. Kaplan finds a mutual culmination in the 1959 collaboration album, Kind of Blue. Completed in only two sessions, it has been the best-selling jazz album ever. While they went onto many creative achievements after that, especially Coltrane’s A Love Supreme, the subtitle’s final words—“the Lost Empire of Cool”—suggests that Kaplan considers Kind of Blue a musical peak for the three, as good as it gets.

The impact of loss comes from the devastated health of these men in their final years. Kaplan captures the desperation of his three principals’ ravaged final days, their driven compulsion to often literally drag themselves onto the stage and perform, in part to earn the money to support their habits, but also in a hunger to continue making music, aware that their final notes loomed.

Coltrane died first. After a biopsy confirmed liver cancer, he denied surgery and “spent miserable weeks thereafter lying on the living room couch, listening to playbacks of recent recording sessions” before his death on July 17, 1967. As Evans was rushed to a hospital, blood spewing from his mouth, his bassist Joe LaBarbera carried him into the emergency room, reporting that “he weighed almost nothing.” Evans died on that September 15, 1980. Down to eighty pounds, Davis fell into a coma. “He never regained consciousness. Three weeks later, on September 28, 1991, he died, a very old (and very young) sixty-five.—”

While Kind of Blue certainly lives on, its creators suffered miserable deaths that were anything but cool. Their music was a triumph that secures their magical legacy. But Kaplan won’t let us forget the price of their legacy of drugs.