Review by Linda Lappin

Thomas E. Kennedy, author of The Copenhagen Quartet, is often considered a “writer’s writer,” one whose name may be known only to a particular niche of readers, but to whom other writers turn for illumination concerning the nuts and bolts of writing – issues of craft as well as of inspiration. His career has been a slow, steady, unstoppable river towards greater recognition. After four decades of small press publications and prestigious awards, at last, in 2010, at the age of sixty-six, he made a quantum leap to a major house –Bloomsbury, which republished all four volumes of his masterful Copenhagen Quartet, originally issued from 2002-2005, by Wynkin DeWorde, an independent Irish press.

For the Bloomsbury imprint, the novels were deeply revised, refurbished with new titles and assigned a new order in the Quartet. Volume 3 of the DeWorde series, Greene’s Summer, was the first to be released by Bloomsbury, now entitled In the Company of Angels. Dealing with the return to life of a Chilean torture victim, it was an instant success, garnering highest praise from the Los Angeles Times, the New Yorker, the Guardian, just to name a few. The other three volumes, all critical successes, followed closely: Falling Sideways (formerly Danish Fall), Kerrigan in Copenhagen (Kerrigan’s Copenhagen) and Beneath the Neon Egg (Bluett’s Blue Hours). Comparing the revisions to the originals is a fascinating study in the art of rewriting and editing for all students of the craft. Kerrigan’s Copenhagen, for example, was completely overhauled and reduced by more than a third of its page count when republished as Kerrigan in Copenhagen.

The Quartet is a metafictional, intertextual, roman fleuve: four independent stories set in the four seasons of Copenhagen, each with a different genre and style – novel of social conscience; effervescent, experimental love story combining philosophical enquiry with a guidebook; office satire; noir. The stories unfold upon the vibrant urban canvas of Copenhagen, in, on, and around real streets, cafes, bars, parks, landmarks, bridges, and apartment buildings so that the city itself could be considered a character in the overall plan, or perhaps, a muse, like Joyce’s Dublin or Durrell’s Alexandria. In all four novels, jazz offers suggestions for plot structure and lends its rhythms to Kennedy’s prose.

The very diverse male protagonists of each of these novels seem to be drawn from Kennedy’s own direct, personal experience – as an expat writer in Denmark, an autumnal lover in search of a meaningful relationship, yet attracted to situations of risk – as well as from his professional life, as a translator working with torture victims in a rehabilitation center (In the Company of Angels), and as a manager in an international firm in the throes of downsizing.

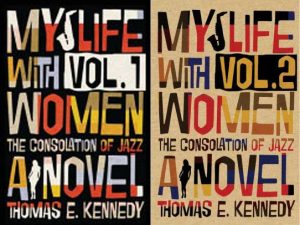

In his new 2 volume semi-autobiographical novel/ fictionalized memoir, My Life with Women, Kennedy pushes autobiographical fiction to its limits – and gives us the backstory of his writing career: the women and the music that provided inspiration; the tangled relationships impossible to fix; the quest to become (and call himself) a real writer, interwoven with many anecdotes of the partners, writers, teachers, publishers, editors, friends, students, agents, reviewers, booksellers, rivals, children, and lovers who accompanied him from the first small press adventures to his international success. While the narrator, Edward Fitzgerald, and some of the characters bear fictionalized names, others are real people with real names whom many readers will recognize. After the first two pages, we sense that this is more than a self-portrait of the artist through the years, and we want to know: Where is the author going with this? How much is real and how much the stuff of fiction?

Two writers come to mind as mentors and models for this latest installment of Kennedy’s ambitious project of transforming life into fiction and fiction into life: Anais Nin and Henry Miller, linked themselves by a literary and sexual passion. Anais Nin, who claimed that her life and writing were inseparable, transmuted her famous diary into fiction through her roman fleuve, following the lives of four women, each of whom represents part of Nin herself. Miller’s work, strongly autobiographical, has been described by one critic as retrieving what “remains of the disappearing past.” For both Nin and Miller, honesty in addressing the darker shades of eros was essential to their work. For both, writing was an exercise in seduction (sometimes of each other) and also a form of spiritual practice. These are tenets with which Kennedy would surely agree.

Like Miller, Kennedy as a story-teller can be, at times, blunt, ribald, witty, wily, naughty, and hilarious, but also tender, philosophical and wise. Like Nin, he can be lyrical, intuitive, and sensitive to the connections between music and writing. Like both Nin and Miller, he is willing to follow the muse wherever she leads, and by the end of Volume 2, she has led him to a most unexpected place where the writing life begins to unravel.

Volume 1 covers the period from age sixteen and his first encounters with the explosive combination of girls, jazz, and writing, to age fifty-six with the end of his loveless marriage as an expat in Copenhagen. Volume 2 opens with 9.11 and ends in 2018, when, for the first time, at seventy-four, with three major relationships come undone, he begins to frequent prostitutes, still longing to worship a female body.

It is also in the latter third of this volume, that, after confronting a frightening health crisis, he finds himself grappling with a writer’s worst nightmare: losing his grip on language. First, his fluency in Danish evaporates- the language which he spoke daily, and from which he translated expertly, disappears from his tongue. He can understand it but no longer speak it. Then words in English scramble when he talks and his memory begins to falter –all due to the pressure of an inoperable brain cyst. And if that weren’t enough, a nasty fall on the metro stairs sends him back to the hospital. While the reader knows that he will get back on his feet, once the broken ankle is mended, we also know that an abyss yawns up ahead and eventually the words will run out altogether.

It’s in these hospital scenes, when, as Sylvia Plath suggests, one has given up one’s body over to the nurses and doctors and it is no longer one’s own anymore – that we see the whole range of his humanness: candid, gentle, randy, embarrassed, nostalgic, soulful, upbeat, depressed, and grateful for the courtesy he receives from friends, strangers, hospital staff. The “courtesy” he prizes echoes D.H. Lawrence’s concept of “tenderness” which the English writer believed infused Etruscan culture, a sensitivity to the environment and to others which when practiced allows us to become truly ourselves leaving others room to flourish.