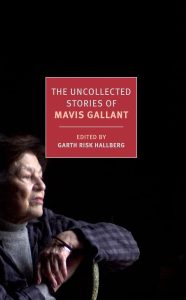

New York Review Books

Review by Walter Cummins

Although the forty-four Mavis Gallant works assembled by editor Garth Risk Hallberg for the 2025 Uncollected Stories had their initial magazine publication in the 1950s and 1960s, they are still as fresh and inventive as they were when new. Gallant stories are unique, like no other writers. That is especially striking because they were written at a time when the well-made Joycean story dominated as a standard, a central character involved in a dilemma that culminates with the surprise of a personal epiphany. It was still the model when Charles Baxter’s objection essay, “Against Epiphanies,” came out in 1997. Yet Gallant had been writing story after story that did not depend on an epiphany long before Baxter attacked the device as cliched and inauthentic.

Gallant’s stories share a distinctive structure, a group of characters with a variety of attitudes assembled in a situation that results in their interaction, leading to a conclusion that resolves the cumulative tension. Each character has thoughts and feelings about a the same matter, unlike the supporting characters in an epiphany story who help dramatize the action that builds to the main character’s illumination with no idea of what’s bothering that character. For the most park, the others are not even aware of the issues the central character is facing. Instead, Gallant’s characters offer a reaction that serves as a commentary on the fundamental situation. Other than the minority of first-person stories, the authorial voice stands outside the characters, commenting on them and the manner in which their perspectives come to shape the possibilities of the situation. The teller of her first-person stories reveals what the others are thinking.

Gallant gives her characters a distinct presence through their feelings about the basic issues of the story. Such feelings and behaviors are revealed in the reactions of the character, often serving as the sources of conflict and tensions, some of which become causes of open or hidden animosities.

Her stories are often edgy in these revelations of her characters’ subjectivity and their inability to settle with their circumstances, often treating her people with a sense of irony at their groping and failures, occasionally to the point where they are judged as comic in their limitations, brought to life by metaphors. A typical example can be found in the way Gallant establishes the interaction of mother and son in “His Mother”: “He was a stone out of a stony generation. Talking to him was like lifting a stone out of water. He never resisted, but if you let go for even a second he sank and came to rest on a dark sea floor.”

Hallberg organizes the contents of The Uncollected Stories by the area of their setting: North America, Southern Europe, Paris and Beyond. Like Gallant who spent her youth adrift in her native Canada and then in her twenties unrooted herself to settle for the rest of her life based in Paris, her characters end up in places away from their origins among others like them seeking a connection to a hoped-for home, some way of making sense of their lives. In “His Mother,” when the son gets his first passport he disappears in Glasgow, Scotland, and “she became another sort of person, an émigré’s mother.”

A representative Gallant story is “The Old Place,” which covers the events of many years and includes the relationship of a group of people to their personal pasts, with the last reaction that of a young man named Dennis, whose past connections no longer exist, the places and people unavailable . The story opens with him as a child being told by his mother how he should revere the black walnut trees that had belonged to his family for generations. But their land had to be sold to a man who cuts them down for more planting space. Dennis retains a strong memory of his mother’s crazed reaction to the cutting even though he realizes he wants the trees to be gone. His father is killed in the Korean War. His European stepfather, Dr. Meyer, who had been in concentration camps during World War II, wants nothing to do with the family property that his wife, Dennis’ mother, still loves.

Dennis is indifferent: “Dennis’s silence was probably owing to the amount of energy he spent trying to resolve the contradictions of life.” He attends a second-rate college to please his mother and accepts Dr. Meyer’s offer to go to Europe and see the camps “without enthusiasm.” In Geneva he meets Meyer’s daughter, Charlotte, who clearly wants no connection with her father. Back in the States, Dennis drops out of college and takes a job in Maine, living with a lively German family in a town of European emigrés: “the most restless people he had ever known,” free of nostalgia, the opposite of his mother and Dr. Meyer. With his mother dead and Dr. Meyer knowing he will be soon, Dennis has no interest is visiting the site of his old home: “There was nothing to go back to there.”

While Dennis may be more overtly lost and alienated than other Gallant characters, he is like many in his realization of displacement and dislocation. Most of her characters are seeking a place where they feel they belong, ending up associating with others equally dislodged. That can be said of those around Dennis in “The Old Place,” each seeking something to hold onto, or—like his stepsister—vehement in the anger of her rejection, while Dennis escapes into an inert passivity. As in a typical Gallant story, everyone has something at stake. As Hallberg indicates in his introduction, this story reveals that “physical and existential dislocation—the state she [Gallant] called being ‘set afloat’—would be revealed as her great subject.”