Wildhouse

Review by Catherine Abbey Hodges

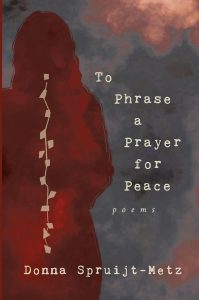

To Phrase a Prayer for Peace, Donna Spruijt-Metz’s second full-length collection of poems, chronicles the poet’s experience of the first 118 days of the Israel-Hamas war. Like so many of us, she followed the catastrophic news from her “unbombed neighborhood,” where she felt increasingly complicit “from this remove / that turns out to be / possible // & unforgivable.” As she tells it in an EcoTheo Collective interview with Hila Ratzabi, on the morning the war began, “I just had to . . . write something down. And I couldn’t stop writing . . . . Every day, another poem. A ‘cryologue’—I think it was Carolyn Forché who coined that phrase.” In the tradition of Forché, with the twist of distance, the result is an almost unbearably relevant book of witness: witness to media coverage, to our nation, to her communities, to her own responses.

The poet herself didn’t at first recognize what she had written as a book. “I thought it was me, agonizing,” she tells Becky Parker of Briar Haus Writes. Indeed, Philip Metres characterizes the poems as “diary poems” (the kind we need more of, he adds, “with their unhardened hearts”) and Yehoshua November refers to the book as a “poetry journal” (an “elegant and moving” one). The unfiltered, spontaneous feel of the poems coupled with the harrowing contemporaneity of the subject matter make for a breathless initial read and, beyond that, imbue the book with a potent afterlife of strange solace and unassuming wisdom.

The collection is comprised of three sections, the first (Prelude—Before the Again) and third (Postlude—It isn’t over) quite brief, with the poems organized chronologically. Every poem in the lengthy second section (Number Our Days—Again) includes in its title the specific day of the war, though after Day 4, many days are skipped on the way to Day 118 and the section’s final poem. The title of the penultimate poem in this section, “Day 110? Day 111? I Looked Away for a Moment,” is an example of the kind of casual, personal disclosure that contributes to the resonance of the poems.

Many of the poems in To Phrase a Prayer for Peace are addressed to YOU, Spruijt-Metz’s name for the numinous. Like the Psalms with which they converse, the poems include expressions of desperation, praise, complaint, complicity, tedium—because even horror waxes tedious—and exhaustion. They’re marked by a startling intimacy: “Don’t / look at me like that” says the speaker to YOU in “Shift,” after Psalm 104, and “Psalm for Day 69” closes with

Maybe I could make YOU

some tea. Do YOU

take honey?

Is there any honey left?

While the Israel-Hamas war is the book’s overt subject, the relationship between the speaker and her YOU is its engine and intrigue.

And here Spruijt-Metz enters a further lineage, that of writings that present conversation or exchange between a mortal and a YOU, a Holy or Divine One. Hafiz, Tu Fu, the Psalmist, Rumi, Rilke, Isaac Luria, Mirabai, Julian of Norwich, Thomas Merton—mystics and contemplatives of all traditions have left records of their experience of and correspondence with the Holy. One such mystic, Hadewijch of Antwerp (1200-1260), wrote of God as “the ravishing far-near” in her native Middle Dutch, producing (per Simon Critchley’s idiosyncratic and encyclopedic book Mysticism) the earliest extant writing by a woman in that vernacular. Like Hadewijch, Spruijt-Metz examines distances and proximities—the “far-near”—in relation to war, complicity, the human and the divine, and does so in a vernacular specific to her life and to our extended moment in time. “Thanksgiving Day, Day 48” reads in its entirety

and we don’t celebrate—

instead, we hold our breaths

clock ticking until

it’s a reasonable time

for a cocktail—ticking

across the expanse

of another unreasonable

day—we wait

for the release—

Time serves not only as the organizing principle of the book but also threads through the collection as a recurring theme, a borderline obsession. Above, the speaker waits for the clock’s ticking to move toward both cocktail hour and the release of hostages; in “Day 118—The Proper Way to Phrase a Prayer for Peace,” she engages in a different kind of waiting. After wondering “What if I ask / for the wrong thing?” she says,

I’m listening to the noise

that the hours make—waiting

for my heart

to soften—waiting

for the ribbons

that bind me

to loosen

and then

I might know

what to ask—and how

to ask for it.

What good fortune for the reader that not knowing what to ask or how to ask for it didn’t deter Spruijt-Metz from writing these poems. In fact, it’s not a stretch to read the book as a restless search for that “what” and “how.” In the process, To Phrase a Prayer for Peace fixes a deeply human gaze on the unbearable dailiness and shocking monotony of war crimes. In their explorations of complicity, fraught and frayed relationships, and the unaccountable persistence of hope, the poems carry on their extended conversation with the Divine in tones of voice all over the map. They do the sustaining, even sacred, work of making something new out of the mess at hand.