New Directions

Review by David Starkey

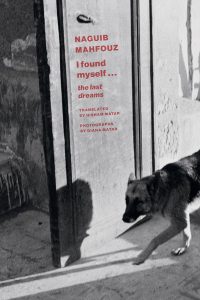

On October 15, 1994, Naguib Mahfouz, the only Egyptian winner of the Nobel Prize in Literature, was on his daily walk in Cairo. “Mahfouz’s regimen was famously predictable,” Hisham Matar, the translator of I Found Myself… The Last Dreams, tells us in his introduction to the book. As a result, it was easy enough for Mahfouz’s would-be killer, an Islamic extremist, to follow the 82-year-old author and stab him repeatedly in the neck.

Matar, along with his wife Diana, met Mahfouz sometime afterwards, in “a secret location” where the author was basically in hiding “due as much to concerns for his safety as…to his waning health: old age had been violently advanced by the assault.” The meeting, which included a number of other writers, made a strong impression on Matar, and he was eager to translate into English Mahfouz’s transcribed dreams, which “grew more vivid, or had come to seem more significant…until his death in 2006.” Mahfouz “would write them down, capturing them in a few swift strokes. He did not only trust his subconscious, he trusted us with it.”

The resulting book is a potpourri of images and encounters. In one dream, Mahfouz is at a protest march, in the next he’s in his childhood home mourning the death of his dog, in the next he’s the owner of a large farm, and in the next he’s boycotting foreign goods while sitting cross-legged on a prayer rug. As with all our dreams, past, present and future collide. The impossible happens matter-of-factly, mingling with the mundane.

The author provides little or no context for the dreams, which are numbered rather than named. Each dream is simply there,then almost immediately it is over. “Dream 226,” for instance, reads in its entirety: “I found myself with a battalion of soldiers in a trench covered with weeds. We waited for the right moment to surprise our enemy, while at the same time fearing that we might be discovered, that tear gas would be hurled into our bunker and we’d die the wretched death of rats.”

Of course, dreams are famously boring for everyone but the dreamer. Can a Nobel Prize winner avoid the dire fate of the self-analyzing narcissist? Mostly the answer is yes. Although Mahfouz was primarily a writer of fiction, his dreams have the quality of brief prose poems. The language is crisp yet evocative. Even when the people mentioned are unfamiliar, the situations themselves resonate. And unlike many people recounting their dreams, Mahfouz knows when to stop. Most of the dreams are just three or four sentences, and none of them go on to a second page.

The text is punctuated with black and white photographs by Diana Matar that do not comment on or even relate to Mahfouz’s entries. Instead, they feel like moments from someone else’s dreams. There’s a blurred street scene with the head of a policeman barely popping above the bottom edge of the photograph. A man stares, haunted, at the camera while behind him passersby traverse a crumbling street. A woman hurries down an alleyway, followed by her shadow. A flock of birds is startled from a tree. Empty railroad tracks are seen through wire mesh. These photographs of Cairo make no attempt to romanticize the place. There are no distant views of pyramids or close-ups of dreamy souks. Instead, Diana Matar’s Cairo is working-class and struggling. She brings out a kind of rough beauty in the city, giving us some visual clues about the sort of things Mahfouz might have seen during his walks during the days before the assassination attempt.

I Found Myself… contains just 99 dreams, and even with the thirty-plus photographs, it’s quite short. Nevertheless, this little book is strangely compelling. I kept returning to it night after night, just before I feel asleep and entered my own, equally strange, dreamworld.