University of North Carolina Press

Review by Brian Tanguay

By the mid-1970s, Charles Diggs Jr. was arguably one of the most powerful members of the House of Representatives. The most senior of the seventeen black members, with many legislative accomplishments and experience working with several presidents. In a quiet but persistent and methodical manner, Diggs had advocated for civil rights, pushed the American airline industry to desegregate, fought for home rule for the District of Columbia, been instrumental in establishing the Congressional Black Caucus, and urged successive administrations to reconceptualize America’s relationship with Africa, particularly the apartheid regime in South Africa. Diggs combined dogged persistence with moral certainty in a way that attracted support from both sides of the political aisle.

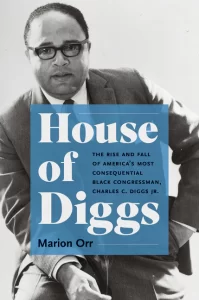

Given these accomplishments, why is Charles Diggs Jr. almost completely forgotten today? This is among the questions that Brown University professor of political science Marion Orr seeks to answer in House of Diggs. Diggs left an impressive trail during his extraordinary life, and this son of Detroit participated in some of the twentieth century’s most important issues. Orr’s research and writing provide a rounded perspective of a complex man, his origins, and the influences that formed his character. While this is a work of history, it’s also a tragedy in the Shakespearean sense.

Only thirty-two when he arrived in Washington in 1955, Diggs became one of the most respected members of Congress, a quietly effective legislator, a coalition builder who practiced a politics of strategic moderation. In our age of political polarization and extremism, strategic moderation sounds quaint, but it was the cornerstone of Diggs’ success. Diggs had a quieter personality than contemporaries like Adam Clayton Powell and William Dawson, but as Orr demonstrates, his accomplishments were more consequential. Diggs played the long game.

Along with being a son of Detroit, Diggs was also a product of the Great Migration. His parents established the House of Diggs funeral home and made a prosperous living; Charles Diggs Senior was the first black Democrat elected to the Michigan State Senate. The Diggs family were members of Detroit’s black elite. At that time, Detroit was a manufacturing colossus and home to a vibrant labor movement. But social prominence in Detroit didn’t shield young Charles from the racism and prejudice of the day. When Diggs enrolled at the University of Michigan in 1940, there were less than one hundred black students in a student body of 25,000. Racism was overt. Most white students wouldn’t even speak to Diggs. Transferring two years later to Fisk University, a historically black university in Nashville, Tennessee, Diggs got a taste of what life was like for black people below the Mason-Dixon line. When his train crossed the line Diggs had to get off and move to a segregated train. This first-hand experience of institutional humiliation was something Diggs never forgot, and more was in store.

At the age of twenty-one, Diggs was commissioned as a second lieutenant in the US Army Air Force. He was the youngest member of his graduating class at a time when blacks accounted for less than one percent of the Army Air Force officer corps. As Orr notes, thousands of black servicemen experienced racism and violence from their fellow citizens during World War II. Even black officers were not spared mistreatment and disrespect. White soldiers often crossed the street to avoid saluting Diggs. At Walterboro Airfield in Alabama, German prisoners of war dined with white soldiers and guards in establishments that refused to serve black servicemen. Even in time of war, segregation was brutal and inescapable.

Orr delves into the circumstances and personal shortcomings that contributed to Diggs’ downfall. For all his experience managing his family’s funeral business, Diggs lacked discipline with money and lived beyond his means; he had a history of womanizing and was married four times; he gambled. In attempting to extricate himself from dire financial straits, Diggs abused the privileges of his congressional office, leading to his indictment in 1978 by a federal jury on twenty-nine felony counts. In 1979, the House of Representatives censured Diggs, stripping him of the committee chairmanships and congressional power he had worked for years to amass. In 1980, Diggs resigned his office.

What then are we to make of the life and political career of Charles Diggs Jr? How should Diggs be remembered? Do his personal failings invalidate his professional accomplishments and justify ignoring or downplaying them? I think Orr gets it right: “Diggs’s story is that of a man who loved his country and who wanted it to live up to its creed of equality; he was an imperfect man who nevertheless responded to a higher calling to serve and enabled genuine and lasting changes on American life.”

House of Diggs is the story of a complex man whose lofty ideals were betrayed by iniquitous impulses. I can’t help but compare Charles Diggs Jr. with contemporary political figures. He admitted that what he had done was wrong and accepted his punishment without excuses, without blaming others, and without claiming to be a victim. For all his failings, Diggs retained a sense of honor. That’s more than can be said for a host of current leaders who pride themselves on never taking responsibility for their actions.