Norton

Review by David Starkey

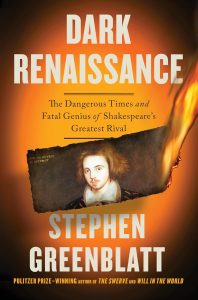

It’s appropriate that the painting on the cover of Stephen Greenblatt’s Dark Renaissance: The Dangerous Times and Fatal Genius of Shakespeare’s Greatest Rival may, or may not, actually be a painting of Christopher Marlowe, the book’s subject. The young man depicted is handsome, with flowing reddish-brown hair and a look of amused irony—and maybe just a touch of disdain. But the portrait, dated 1585, wasn’t discovered until 1952, when workers at Cambridge’s Corpus Christi College were doing renovation work. The renovated room was above the one Marlow had once lived in, but the painting is unsigned and there is no indication of its subject’s name. Attributing it to Marlowe is essentially the result of some very intelligent guesswork, and the same could be said of much of Greenblatt’s biography.

There are some facts that historians and literary scholars agree upon. Marlowe was born the impoverished son of a Canterbury shoemaker in 1564, he attended Cambridge University on a scholarship, and he was stabbed to death in a tavern in Deptford in 1593. He is the author of a number of poems, most famously “The Passionate Shepherd to His Love” (which provoked an extremely sardonic response from Sir Walter Ralegh), and a handful of plays, including Tamburlaine the Great, the first play in English to employ blank verse with unquestionable success, The Jew of Malta, Doctor Faustus and Edward II. His plays, Greenblatt argues, stand alone as great works of literature, but we also turn to them because Marlowe clearly influenced the work of his more famous, and longer-lived, contemporary, William Shakespeare.

In addition to legal documents, Greenblatt uses the plays to work outward to biography. So, for example, when he is discussing Doctor Faustus, he finds qualities in Faust that can also be attributed to Ralegh: both were dashing, adventurous, egotistical and, in Ralegh’s case reputedly, blasphemous. Similarly, in Henry Percy, the fabulously wealthy 9th Earl of Northumberland, Greenblatt sees a parallel between Faust’s and Percy’s insatiable thirst for knowledge in every field, from philosophy and religion to geography and the natural sciences. Marlowe may, or may not, have been familiar with these two worthies, but Greenblatt provides substantial evidence that he was, then he goes on to consider how they might have influenced the young, ambitious dramatist.

It might all sound a bit far-fetched, but Greenblatt is such a persuasive proponent for his conclusions that his speculations and intuitions feel almost like settled fact. Moreover, he is such a gifted writer that at times Dark Renaissance reads like a thoroughly researched historical novel with wonderfully over the top characters, albeit one without much dialogue.

Greenblatt, of course, is not the first author to be attracted by the gaping holes in Marlowe’s life story. The Marlowe Society lists half a dozen biographies written in the last twenty-five years. What makes Greenblatt’s special is that he also one of the world’s premier Shakespeare scholars, so he already knows the Elizabethan world intimately. And a treacherous place it was, with armies of spies—by all accounts Marlowe was one of them—and the sort of backstabbing and betrayal that make Mean Girls look like an episode of My Little Pony.

In fact, the aspect of Marlowe’s life that most seems to fascinate his biographers is his death. “That Marlowe was killed is certain,” Greenblatt writes. “But everything else about the events…on May 30, 1593, is open to question.” We know that, to save his own skin, fellow playwright Thomas Kyd accused Marlowe of atheism and treason, which Greenblatt, and others, reckon led to Marlowe being lured to a tavern in a dockside town southeast of London. There things get fuzzy, as the only document we have was the inquest, which was provided by the very people who are suspected of entrapping and murdering Marlowe. For Greenblatt, the mostly likely scenario involves a day of drinking followed by an orchestrated effort by three of Her Majesty’s spies to get the quick-tempered Marlowe to attack one of them so that he could be killed in an act of “self-defense.”

But if the exact hows and whys of Marlowe’s death remain unsettled, Greenblatt has no doubt about his subject’s greatness as an author: “Marlowe was a genius but a profoundly disturbing one. His plays themselves were provocations. They said things about power, about money, about Jews, about hell, about God, and about sex that had never been said before, at least in public. Above all, they said them with startling frankness and a stupendous, unheard-of eloquence.”

I must admit I had not read Marlowe’s plays since I was an undergraduate. Did Dark Renaissance make me want to head to the nearest bookseller and buy his Complete Plays immediately? Indeed, it did.